Witchcraft

Today’s episode is on one of the best topics ever – the history of witchcraft!

We start this episode by looking at the first famous witchcraft trial (and pamphlet) in England, the case of Mother Waterhouse. Mother Waterhouse’s case gives us some clues as to why witches and witchcraft-accusers tended to be women. One reason is that witchcraft cases tended to revolve around neighborly disputes, household problems and children. Because of this, we’ll see the witch portrayed as the “anti-housewife” and the “anti-mother.”

Then, we’ll look at how witchcraft was prosecuted in the courts. How can you prove that someone is a witch? Many types of evidence are brought before the courts, including children having fits, some extremely doubtful testimony, and the witch’s mark. Over time, the evidence becomes too doutbful to trust and witchcraft becomes impossible to prove by the late-seventeenth century.

Finally, we’ll bring it all back to the history of murder. How does witchcraft match up against other “feminine” crimes we’ve seen so far?

And yes, it’s true that witchcraft isn’t classically considered a type of homicide. But how could I resist?

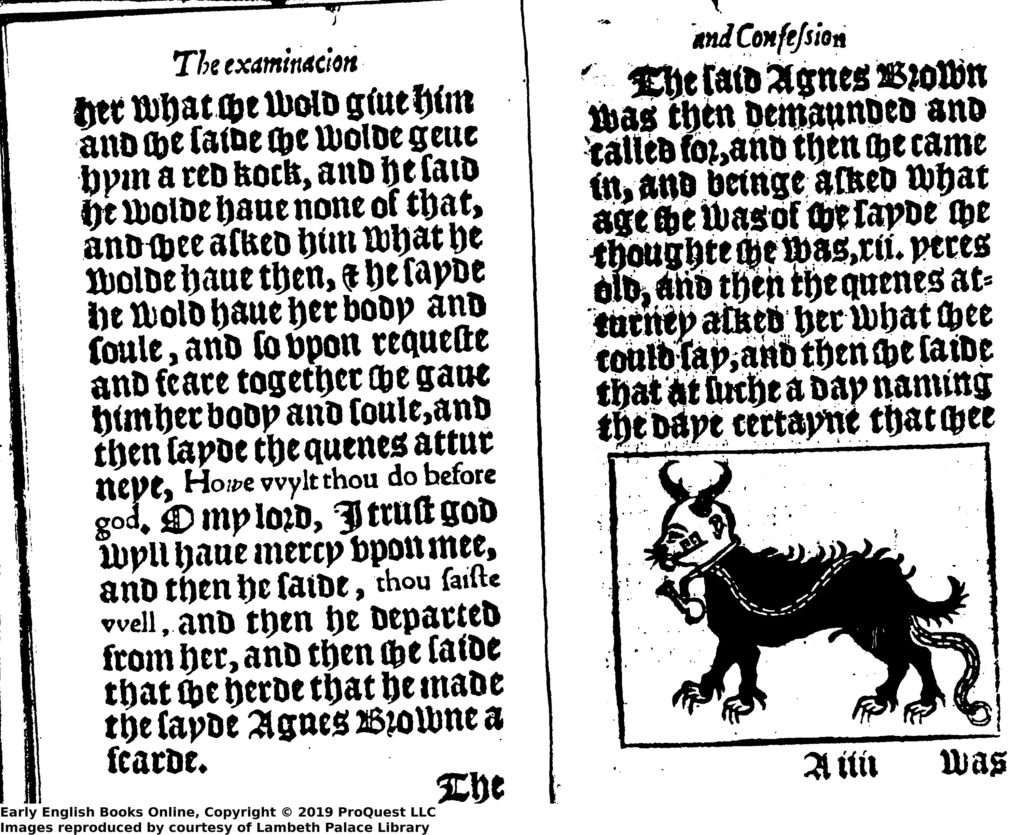

The Mother Waterhouse Pamphlet, depicting Satan as a dog with an ape face, horns, and a whistle around his neck.

Sources:

The pamphlet’s full name is The examination and confession of certaine wytches at chensforde in the countie of essex : Before the quenes maiesties judges, the xxvi daye of july, anno 1566, at the assise holden there as then, and one of them put to death for the same offence, as their examination declareth more at large, printed 1566. London, By Willyam Powell for Wyllyam Pickeringe.